INDEX of Volume 1

1) History Of Portsmouth - England, Its Famous People And Events

2) History of The Mary Rose 1509, HMS Victory 1759 and HMS Warrior 1859

3) Havant Market Town – England and It's History

4) Chichester Market Town – England and it's History

5) A to Z of English and Welsh Market Towns

6) The Victoria Cross – It's History

7) English Wine and It's History

8) History of The 17th Century Corkscrew – England

9) English Morris Dancing – History

10) History of the English Constitution AD 890 to Present day

11) English Kings and Queens from 774 AD to Present Day

12)The English Translated Magna Carta

13) List of British Royal Societies

14) History of British Police and Funny Art

15) England's Trial by Jury

16) English Tea Drinking Traditions – History

17) English Toby Jugs – History

18) English Cathedrals from 300 AD to Present Day

19) The First Powered Passenger Car and Bus – England 1801

20) My Favorite British Iconic Cars

21) History of The Hovercraft

22) The World's First Electric House – England 1878

23) English Speaking Countries

24) English Crop Circles – The History From 1115 AD

25) Halloween – It's English Celtic History

26) My Supernatural Experiences

History Of Portsmouth - England, Its Famous People And Events

I was born in Portsmouth in 1961 ( Exactly a year to the day after my brother was born).

The history of Portsmouth is entwined with the history of Her Majesty's Naval Base Portsmouth which extends almost two thousand years. The time when the Romans first recognized its strategic significance and built the fort "Portus Adurni", and now the home to 80% of the Royal Navy's surface fleet.

As so many Famous events and People were Born, Lived and worked in Portsmouth over the centuries I thought it would be a good idea to tell its story and some of the famous people's history.I shall be adding to this article and the many other articles that I have written with updates and Pictures - so please bookmark my site and return often.

Badminton Association

The first British Badminton Association was founded in Waverley Grove, Portsmouth in 1893.

Marc Bolan - T Rex

The last UK Concert by T-Rex and Marc Bolan was in 1977 at The Guildhall, Portsmouth. As an interesting addendum Marc Bolan's brother worked for many years as a Portsmouth Bus Conductor.

HMS Pinafore by Gilbert and Sullivan

The Comic Opera HMS Pinafore by Gilbert and Sullivan was set in and around Portsmouth and its Harbour.

Mrs Duncan – The Last Witch to be Tried as a Witch

The last person to be tried as a witch was a Mrs Helen Duncan, a Scotswoman who travelled the country holding seances, was one of Britain's best-known mediums, reputedly numbering Winston Churchill and George VI among her clients, when she was arrested in January 1944 by two naval officers at a seance in Portsmouth. The military authorities, secretly preparing for the D-day landings and then in a heightened state of paranoia, were alarmed by reports that she had disclosed - allegedly via contacts with the spirit world - the sinking of two British battleships long before they became public. The most serious disclosure came when she told the parents of a missing sailor that his ship, HMS Barham, had sunk. It was true, but news of the tragedy had been suppressed to preserve morale.

Desperate to silence the apparent leak of state secrets, the authorities charged Mrs Duncan with conspiracy, fraud, and with witchcraft under an act dating back to 1735 - the first such charge in over a century. At the trial, only the "black magic" allegations stuck, and she was jailed for nine months at Holloway women's prison in north London. Churchill, then prime minister, visited her in prison and denounced her conviction as "tomfoolery". In 1951, he repealed the 200-year-old act, but her conviction stood.

Wymering Manor House – The Most Haunted House in England.

As I am from Portsmouth, England I thought it may be of interest to write about the oldest house in Portsmouth and the most haunted house in England, called “Wymering Manor House” and dated from 1042 AD.

Although most of the current structure dates back to the 16th century, the manor goes back much further. Records show the first owner of Wymering Manor was King Edward the Confessor in 1042 and then after the Battle of Hastings it fell into the hands of King William the Conqueror until 1084. The house has been altered and renovated continually over the centuries, yet remarkably it has retained materials dating back to medieval and even ancient Roman times.

Having changed ownership many times over these hundreds of years, the property was eventually adopted by the Portsmouth City Council, then sold for a short time to a private organization for development into a hotel. When the development fell though, the property reverted to the council, which has again put it up for auction.

Once a country manor, the structure is now surrounded by modern houses. And when it was saved from demolition and used as a youth hostel, many areas of the building were "modernized" and have an unfortunate, institutional feel.

With this rich history it's no surprise perhaps that Wymering Manor should be haunted.

Below are some of the Ghosts that haunt Wymering Manor:

The Lady in the Violet Dress. When Mr. Thomas Parr lived at Wymering Manor, he awoke one night to the sight of an apparition standing at the foot of his bed. It was his cousin, who had died in 1917. Dressed in a full-length violet-coloured dress, the spirit spoke to him in a friendly and matter-of-fact manner, telling him of her recent religious experiences and about other deceased family members. Suddenly the ghost said, "Well, Tommy dear, I must leave you now as we are waiting to receive Aunt Em." In the morning, Parr received a telegram with the news that his Aunt Em had died during the night.

The Blue Room. An elderly relative of Thomas Parr, who was staying in the "Blue Room," was careful always to lock her door at night, as she feared break-ins by burglars. One morning she was surprised to find her door unlocked and open.

The Choir of Nuns. Mr. Leonard Metcalf, an occupant of the house who died in 1958, said he occasionally saw a choir of nuns crossing the manor's hall at midnight. They were chanting, he claimed, to the clear sound of music. His family never believed his story as they didn't know - and neither did Mr. Metcalf - that nuns from the Sisterhood of Saint Mary the Virgin visited the house in the mid-1800s.

The Panelled Room. The so-called "Panelled Room" may be the manor's most dreaded. The Panelled Room served as a bedroom in the manor's south east corner, and as Metcalf was using the washbasin one day, he was startled by the distinct feeling of a hand on his shoulder. He turned quickly to find no one there. Others have felt an oppressive air in this room, instilling a strong feeling to flee. When the building served as the youth hostel, its warden and wife expressed an unexplained fear of the room.

Other Paranormal occurrences reported at the manor include visitors who claim to have heard the whispers of children, spotted strange apparitions and seen items in the manor move of their own accord. Dramatic drops in temperature and accounts of unusual or intimidating 'spirit energies' have also been reported. Film and video footage has captured both orbs and other strange light anomalies.

Buckingham, George Villiers,1592 to 1628

IN THIS HOUSE GEORGE VILLIERS DUKE OF BUCKINGHAM WAS ASSASSINATED BY JOHN FELTON 23RD AUG 1628

1st duke of (vil'yurz, bŭk'ing-um) [key], English courtier and royal favourite.

While organizing a second campaign he was stabbed and killed at the high street, Old Portsmouth on August 23, 1628 by John Felton, an army officer who had been wounded in the earlier military adventure. Felton was hanged in November and Buckingham was buried in Westminster Abbey. His tomb bears a Latin inscription translating: "The Enigma of the World" and was also one of the most rewarded royal courtiers in all history.

The romantic aspects of the duke's career figure largely in Alexander Dumas's historical novel, The Three Musketeers. The Duke of Buckingham died leaving his wife Katherine Manners, their daughter Mary and son George, 1628.

Admiral Lord George Anson ( April 23rd. 1697 - 1762 )

George Anson, 1st Baron Anson was a British admiral and a wealthy aristocrat, noted for his circumnavigation of the globe.

Sailed around the world between 1740-1744 on HMS Centurion and brought back 500,000 pounds sterling value of Gold ( Equivalent in todays money 250 Million Pounds!!) as Booty from the Spanish in South America.

Jonas Hanway (1712-1786)

Born in Portsmouth & Pioneer of Umbrella.

English traveler and philanthropist, was born at Portsmouth in 1712.

He was the founder of the Magdalen Hospital and has the credit of being the first man who ventured to dare public reproach and ridicule by carrying an umbrella habitually in London. As he died in 1786, and he is said to have carried an umbrella for thirty years, the date of its first use by him may be set down at about 1750.

While still a child, his father, a victualer, died, and the family moved to London. In 1729 Jonas was apprenticed to a merchant in Lisbon. In 1 743, after he had been some time in business for himself in London, he became a partner with Mr Dingley, a merchant in St Petersburg, and in this way was led to travel in Russia and Persia. Leaving St Petersburg on the 10th of September 1743, and passing south by Moscow, Tsaritsyn and Astrakhan, he embarked on the Caspian on the 22nd of November, and arrived at Astrabad on the 18th of December. He was the first Londoner, it is said, to carry an umbrella and he lived to triumph over all the hackney coachmen who tried to hoot and hustle him down.

Lord Admiral Nelson ( 1758-1805 )

HMS Victory in Dock without Sails Portsmouth Coaching Inn where Nelson and Lady Hamilton stayed prior to Trafalger 1805.

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, KB (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British admiral famous for his participation in the Napoleonic Wars, most notably in the Battle of Trafalgar, a decisive British victory in the war, during which he lost his life.[1] Nelson was noted for his considerable ability to inspire and bring out the best in his men, to the point that it gained a name: "The Nelson Touch".

His actions during these wars meant that before and after his death he was revered like few military figures have been throughout British history.

During the 18th century, even though he had been married for some time, Nelson became famous for his love affair with Emma, Lady Hamilton, the wife of the British Ambassador to Naples and she became Nelson's mistress, returning to the United Kingdom to live openly with him, and eventually they had a daughter, Horatia. It was the public knowledge of this affair that induced the Navy to send Nelson back out to sea after he had been recalled. By his death in 1805 Nelson had become a national hero, and he was given a State Funeral. To this day his memory lives on in numerous monuments, the most notable of which is London's Nelson's Column, which stands in the centre of Trafalgar Square.

John Pounds (1766-1839)

John Pounds was born in Portsmouth on 17th June 1766. His father was a sawyer in the royal dockyard and when was twelve years old, his father arranged for him to be apprenticed as a shipwright. Three years later John fell into a dry dock and was crippled for life.

Unable to work as a shipwright, John became a shoemaker and by 1803 had his own shop in St. Mary Street, Portsmouth. While working in the shop, John began teaching local children how to read. His reputation as a teacher grew and he soon had over 40 pupils attending his lessons. Unlike other schools, John did not charge a fee for teaching the poor of Portsmouth. As well as reading and arithmetic, John gave lessons in cooking, carpentry and shoe making. John Pounds died in 1839.

Charles Dickens 1812 – 1870

Birthplace of Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens was born in Landport, Portsmouth in Hampshire, the second of eight children to John Dickens (1786–1851), a clerk in the Navy Pay Office at Portsmouth, and his wife Elizabeth Dickens (née Barrow, 1789–1863).

When he was five, the family moved to Chatham, Kent. In 1822, when he was ten, the family relocated to 16 Bayham Street, Camden Town in London.

Charles Dickens published over a dozen major novels, a large number of short stories (including a number of Christmas-themed stories), a handful of plays, and several nonfiction books. Dickens's novels were initially serialised in weekly and monthly magazines, then reprinted in standard book formats.

The travelling shows were extremely popular and, after three tours of British Isles, Dickens gave his first public reading in the United States at a New York City theatre on 2 December 1867.

On 9 June 1870, he died at home at Gad's Hill Place after suffering a stroke, after a full, interesting and varied life. He was mourned by all his readers.

Jeremiah Chubb (1793-1860) and Charles Chubb (1779-1846)

Both brotherswere born, lived and worked in Portsmouth & are Famous Chubb Locksmiths.

The name of Chubb is famous in the lock world for the invention of the detector lock and for the production of high quality lever locks of outstanding security during a period of 140 years. The detector lock was patented in 1818 by Jeremiah Chubb of Portsmouth, England, who gained the reward offered by the Government for a lock which could not be opened by any but its own key. It is recorded that, after the appearance of this detector lock, a convict on board one of the prison ships at Portsmouth Dockyard, who was by profession a lockmaker, ad had been employed in London in making and repairing locks, asserted that he had picked with ease some of the best locks, and that he could pick Chubb's lock with equal facility. Improvements in the lock were subsequently made under various patents by Jeremiah Chubb and his brother Charles.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel ( 1806-1859 )

Famous photo of Isambard Kingdom Brunel Plaque where His House used to be Portsmouth monument to IKB

Brunel, perhaps, was the most prodigious Engineer of his time and many of his works, which challenged and inspired his colleagues during this period, have survived to our own time and some are still in use.

He was born in 1806, the son of a distinguished French engineer, Sir Marc Brunel, who had come to England at the time of the French Revolution. Unlike most engineers of the time, Isambard Brunel received a sound education and practical training - partly in France - before entering his father's office and taking full charge of the Thames Tunnel at Rotherhithe when he was only 20.

At the age of 26, he was appointed Engineer to the newly-formed Great Western Railway and acted with characteristic boldness and energy. His great civil engineering works on the line between London and Bristol, are used by today's high-speed trains and bear witness to his genius He eventually engineered over 1,200 miles of railway, including lines in Ireland, Italy and Bengal. Each of his three ships represented a major step forward in naval architecture.

Brunel's other works included docks, viaducts, tunnels and buildings and the remarkable prefabricated hospital, with its air-conditioning and drainage systems for use in the Crimean War. Inevitably, in such a prolific career, there were setbacks and disappointments such as the atmospheric railway but he readily admitted his mistakes. Indeed he himself suffered financially by supporting his ventures with his own money.

Brunel suffered several years of ill health, with kidney problems, before a stroke at the age of 53. Brunel was said to smoke up to 40 cigars a day and to sleep four hours each night.

George Meredith (1828-1909)

Famous Novelist & Poet who was born in Portsmouth.

Contributed poems to various periodicals; an associate of the Pre-Raphaelite group around Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Algernon Swinburne; published

the poem Modern Love 1862; author of several novels including Diana of the Crossways 1885, which first brought him popular acclaim.

George Vicat Cole (1833-1893)

George Vicat Cole (usually known as Vicat Cole) was an important landscape painter working in the mid-19th century. In keeping with the realist mood of that period, he painted naturalistic English landscape scenes, without attempting deeper meanings or looking for rustic ideals. His speciality was the effect of atmosphere and light.

Cole was born in Portsmouth, and trained in the studio of his father George Cole (1810-1883), an eminent painter of landscapes, animals and portraits who rose as far as the Vice-Presidency of the Society of British Artists. As a young man, Cole copied prints of works of Turner, Constable and Cox, and the paintings of these men had a strong influence on him.

Lionel William Wylie (1851-1931)

Famous Marine Artist who Lived and died in Portsmouth. Wylie was born into a family of artists in 1851. The rather bohemian family spent their summers on the coast of northern France. Wylie recalled the journey by steamer down the crowded Thames from London on their way to Boulogne. When he was about 12 he went to art school in London, and in 1866 he started at the Royal Academy School. In 1869 he won the Turner Gold Medal for landscape. In 1870 one of the first pictures he exhibited at the Royal Academy was London from the Monument, a panoramic view of the city and the river and he began working as an illustrator of maritime subjects for The Graphic magazine. He had to reproduce detail accurately in black and white, and this discipline probably influenced him when he began making etchings in the early 1880s. Wyllie's first known etching, made in 1884, is Toil, glitter, grime and wealth on a flowing tide. It was commissioned by the print publisher Robert Dunthorne. Wyllie's Thames pictures led him to be elected an Associate of the Royal Academy in 1889. By 1907, when he became a Royal Academician, he had moved to a house at the entrance of Portsmouth Harbour. He had largely turned to painting naval and historical subjects. Nevertheless, he continued to make prints of London and the Thames to the end of his life.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle ( 1859-1930 )

Plaque where Arthur Conan Doyle used to have his surgery.

Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle was born on May 22, 1859, in Edinburgh, Scotland. The Doyles were a prosperous Irish-Catholic family, who had a prominent position in the world of Art. Charles Altamont Doyle, Arthur's father, a chronic alcoholic, was the only member of his family, who apart from fathering a brilliant son, never accomplished anything of note. At the age of twenty-two, Charles had married Mary Foley, a vivacious and very well educated young woman of seventeen.

Mary Doyle had a passion for books and was a master storyteller. Her son Arthur wrote of his mother's gift of "sinking her voice to a horror-stricken whisper" when she reached the culminating point of a story. There was little money in the family and even less harmony on account of his father's excesses and erratic behavior. Arthur's touching description of his mother's beneficial influence is also poignantly described in his biography, "In my early childhood, as far as I can remember anything at all, the vivid stories she would tell me stand out so clearly that they obscure the real facts of my life."

After Arthur reached his ninth birthday, the wealthy members of the Doyle family offered to pay for his studies. He was in tears all the way to England, where for seven years he had to go to a Jesuit boarding school. Arthur loathed the bigotry surrounding his studies and rebelled at corporal punishment, which was prevalent and incredibly brutal in most English schools of that epoch.

During those grueling years, Arthur's only moments of happiness were when he wrote to his mother, a regular habit that lasted for the rest of her life, and also when he practiced sports, mainly cricket, at which he was very good.

The young medical student met a number of future authors who were also attending the university, such as for instance James Barrie and Robert Louis Stevenson. But the man who most impressed and influenced him, was without a doubt, one of his teachers, Dr. Joseph Bell. The good doctor was a master at observation, logic, deduction, and diagnosis. All these qualities were later to be found in the persona of the celebrated detective Sherlock Holmes.

A couple of years into his studies, Arthur decided to try his pen at writing a short story. Although the result called The Mystery of Sasassa Valley was very evocative of the works of Edgar Alan Poe and Bret Harte, his favorite authors at the time, it was accepted in an Edinburgh magazine called Chamber's Journal, which had published Thomas Hardy's first work.

Dr. Arthur Conan Doyle's first gainful employment after his graduation was as a medical officer on the steamer Mayumba, a battered old vessel navigating between Liverpool and the west coast of Africa. Unfortunately he found Africa as detestable as he had found the Arctic seductive, so he gave-up that position as soon as the boat landed back in England. Then came a short but quite dramatic stint with an unscrupulous doctor in Plymouth of which Conan Doyle gave a vivid account of forty years later in The Stark Munro Letters. After that debacle, and on the verge of bankruptcy, Conan Doyle left for Portsmouth, to open his first practice.

He rented a house but was only able to furnish the two rooms his patients would see. The rest of the house was almost bare and his practice was off to a rocky start. But he was compassionate and hard working, so that by the end of the third year, his practice started to earn him a comfortable income.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle also became one of the first goalkeepers of Portsmouth Football club in the 1880s.

Arthur Conan Doyle died on Monday, July 7, 1930, surrounded by his family. His last words before departing for "the greatest and most glorious adventure of all," were addressed to his wife. He whispered, "You are wonderful."

Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936)

Who lived in Portsmouth and also attended School in Portsmouth.

Kipling's days of "strong light and darkness" in Bombay were to end when he was six years old. As was the custom in British India, he and his three-year-old sister, Alice ("Trix"), were taken to England—in their case to Southsea (Portsmouth), to be cared for by a couple that took in children of British nationals living in India. The two children would live with the couple, Captain and Mrs. Holloway, at their house, Lorne Lodge, for the next six years. In his autobiography, written some 65 years later, Kipling would recall this time with horror, and wonder ironically if the combination of cruelty and neglect he experienced there at the hands of Mrs. Holloway might not have hastened the onset of his literary life.

Kipling kept writing until the early 1930s, but at a slower pace and with much less success than before. He died of a hemorrhage from a perforated duodenal ulcer on 18 January 1936, two days before George V, at the age of 70.

Herbert George Wells (1866 – 1946), known as H.G. Wells

Saint Paul's Road, Southsea where HG Wells used to work at a Draper's Shop 1881-1883

Was an English writer best known for such science fiction novels as The Time Machine, The War of the Worlds, The Invisible Man, The First Men in the Moon and The Island of Doctor Moreau. He was a prolific writer of both fiction and non-fiction, and produced works in many different genres, including contemporary novels, history, and social commentary. He was also an outspoken socialist. His later works become increasingly political and didactic, and only his early science fiction novels are widely read today. Both Wells and Jules Verne are sometimes referred to as "The Father of Science Fiction".

No longer able to support themselves financially, the family instead sought to place their boys as apprentices to various professions. From 1881 to 1883 Wells had an unhappy apprenticeship as a draper at the Southsea Drapery Emporium. His experiences were later used as inspiration for his novels The Wheels of Chance and Kipps, which describe the life of a draper's apprentice as well as being a critique of the world's distribution of wealth.

In 1883, Wells's employer dismissed him, claiming to be dissatisfied with him. The young man was reportedly not displeased with this ending to his apprenticeship. Later that year, he became an assistant teacher at Midhurst Grammar School, in West Sussex (teaching students such as A.A. Milne, until he won a scholarship to the Normal School of Science (later the Royal College of Science, now part of Imperial College London), studying biology under T. H. Huxley. As an alumnus, he later helped to set up the Royal College of Science Association, of which he became the first president in 1909.

Neville Shute (1899-1960)

Famous Author/Aero-Engineer who worked in Portsmouth.

Born in Somerset Road, Ealing, London, he was educated at the Dragon School, Shrewsbury School and Balliol College, Oxford. Shute's father, Arthur Hamilton Norway, was the head of the post office in Dublin in 1916 and Shute was commended for his role as a stretcher bearer during the Easter Rising. Shute attended the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich but because of his stammer was unable to take up a commission in the Royal Flying Corps, instead serving in World War I as a soldier in the Suffolk Regiment. An aeronautical engineer as well as a pilot, he began his engineering career with de Havilland Aircraft Company but, dissatisfied with the lack of opportunities for advancement, took a position in 1924 with Vickers Ltd., where he was involved with the development of airships. Shute worked as Chief Calculator (stress engineer) on the R100 Airship project for the subsidiary Airship Guarantee Company. In 1929, he was promoted to Deputy Chief Engineer of the R100 project under Sir Barnes Wallis.

Sir Walter Besant (14-08-1836 to 9-06-1901)

Famous Novelist/Scientist and historian from London. His sister-in-law was Annie Besant.

The son of a merchant, he was born at Portsmouth, Hampshire and attended school at St Paul's, Southsea, Stockwell Grammar, London and King's College London. In 1855, he was admitted as a pensioner to Christ's College, Cambridge, where he graduated in 1859 as 18th wrangler. After a year as Mathematical Master at Rossall School, Fleetwood, Lancashire and a year at Leamington College, he spent 6 years as professor of mathematics at the Royal College, Mauritius. A breakdown in health compelled him to resign, and he returned to England and settled in London in 1867. He took the duties of Secretary to the Palestine Exploration Fund, which he held 1868–85. In 1871, he was admitted to Lincoln's Inn.

Besant was a Freemason, serving as Master Mason in the Marquis of Dalhousie Lodge, London from 1873. He conceived the idea of a Masonic research lodge, the Quatuor Coronati Lodge of which he was first treasurer from 1886.

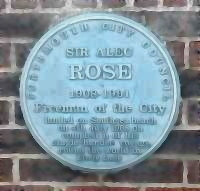

Sir Alec Rose (13 July 1908 - 11 January 1991)

Was a nursery owner and fruit merchant in Portsmouth England who lived at 38 Osborne Road, Southsea who had a passion for amateur single-handed sailing, for which he was ultimately knighted on the beach at Southsea.

Alec Rose was born in Canterbury. During World War II he served in the British Navy as a diesel mechanic on a convoy escort, the HMS Leith. In 1964, Rose participated in the second single-handed transatlantic race, placing fourth across the line in his 36 foot cutter Lively Lady, originally built of paduak by Mr. Cambridge, the previous owner, in Calcutta.

Rose then modified the boat, including the addition of a mizzenmast, to sail single-handed around the world. He attempted to start this journey at2 approximately the same time as Francis Chichester sailing Gypsy Moth IV in 1966, but a series of misfortunes delayed Rose's departure until the following year. The journey was closely followed by the British and international press, and culminated in his successful return in Portsmouth on July 4, 1968, 354 days later, to cheering crowds of hundreds of thousands. The following day he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II, and nine days later he turned 60 years old. His voyages are detailed in his book "My Lively Lady."

On 17 December 1967, the then Australian Prime Minister, Harold Holt, drove with some family members to Port Phillip Heads, south of Melbourne, to view Rose complete this leg of his voyage. Holt then went for a swim at nearby Cheviot Beach, but the surf was rough, he disappeared from view, and was presumed to have drowned.

Arnold Schwarzenegger (b 1947),

When I was growing up in portsmouth in the 1960s and 1970s most people had heard of the Austrian bodybuilder - Arnold Schwarzenegger the actor and ex. Governor of California - who used to work out in a gym in Albert Road, Southsea with the owner Mr. Wilson who also helped train him win various Body Building Titles.

Henry Ayers (1821-1897)

Who was born in Portsmouth and was an early Premier of the colony of South Australia and the famous Ayers Rock was named after him.

Paul Jones (b 1942),

Was born in Portsmouth in 1942 and was the vocalist with Manfred Mann and latterley also a solo singer and radio presenter.

Brian Howe (born 22nd July 1953)

Brian Howe was the lead vocalist with bad Company and was born in Portsmouth in 1953.

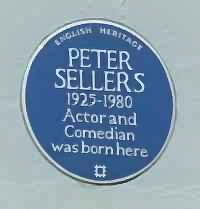

Peter Sellers (8th September 1925 – 24th. July 1980)

The Famous international Comic Actor was born at 96 Castle Road in Southsea, Portsmouth in 1925, whose full name was Richard Henry which his parants always called him Peter after his elder stillborn brother.

Sir Francis Austen (1774 – 1865)

Sir Francis Austen was the brother of Jane Austen and Admiral of the fleet who lived and worked in Portsmouth.

Callaghan of Cardiff,Leonard James Callaghan,Baron and ex. British Prime Minister (1912-2005)

Portsmouth Grammer School

Born in Portsmouth and schooled at Portsmouth Grammer School. He was first elected to Parliament as a Labour member in 1945. As chancellor of the exchequer (1964–67), he introduced extremely controversial taxation policies, including employment taxes; he resigned when he was forced to accept devaluation of the pound. Prime Minister Harold Wilson Wilson, Harold (James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx), 1916–95, British statesman. A graduate of Oxford, he became an economics lecturer there (1937) and a fellow of University College (1938).

Callaghan served as foreign secretary (1974–76). He succeeded Wilson when the latter resigned as prime minister in 1976. Callaghan was by nature a moderate man, but his government was plagued by inflation, unemployment, and its inability to restrain trade unions' wage demands, and foundered after a series of paralyzing labor strikes in the winter of 1978–79. In the elections later in 1979, the Labour party lost to the Conservatives, led by Margaret Thatcher, Margaret Hilda Roberts Thatcher, Baroness, 1925–, British political leader.

Portsmouth Football Club ( Pompey )

Portsmouth F.C. was founded in the back garden of 12 High Street, Old Portsmouth on 5th April 1898 with John Brickwood, owner of the local Brickwoods Brewery as chairman and Frank Brettell as the club's first manager. Portsmouth F.C. is an English football club based in the city of Portsmouth. The city and hence the club are nicknamed Pompey and sometimes called 'The Blues', with fans known across Europe. Pompey were early participants in the Southern League, One of their first Goalkeepers Pre -1898 was Arthur Conan Doyle the author of Sherlock Holmes.

The club joined the Southern League in 1898 and their first league match was played at Chatham Town on 2nd September 1899 (a 1–0 victory), followed three days later by the first match at Fratton Park, a friendly against local rivals Southampton, which was won 2–0, with goals from Dan Cunliffe (formerly with Liverpool) and Harold Clarke (formerly with Everton.

That first season was hugely successful, with the club winning 20 out of 28 league matches, earning them the runner-up spot in the league. During 1910-11 saw Portsmouth relegated, but with the recruitment of Robert Brown as manager the team were promoted the following season.

The team play in the Football League Championship after being relegated from the Premier League after the 2009/10 season. Until then, Portsmouth had been a member of the Premier League for seven consecutive seasons.

Portsmouth's debut season in the English First Division was during the 1920's that alas, turned out to be a difficult one. However, despite disappointing league form the club fought off stiff competition to reach the FA Cup final closely losing out to Bolton Wanderers.

Having solidified their position in the top flight, the 1938-1939 season saw Portsmouth again reach the FA Cup final. This time Portsmouth were successful beating Wolves in a convincing 4-1 win. The club had secured their first major trophy.

After the end of World War Two league football began again and Portsmouth quickly proved to the footballing masses that they were a team to be reckoned with, lifting the League title in 1949 season. The club then crowned this achievement by retaining the title the following year 1950 and becoming only one of five English teams to have won back to back championships since World War Two.

Portsmouth was the first club to hold a floodlit Football League match when they played Newcastle in 1956.

Finally under the management of Harry Redknapp Portsmouth were promoted into the Premier League and have held a solid place in the top flight since this date despite coming close to relegation a number of times.

Portsmouth went from strength to strength under the careful management of Harry Redknapp and a much-needed injection of cash. In the 2007-2008 season Portsmouth won the English F.A. Cup and qualified for the UEFA Cup qualification. They had proven themselves as a consistent and strong team.

Alas during the 2009-2010 season they had financial difficulties and were at the root of the Premier League because of there financial difficulties they were deducted 9 points due to going into Administration and subsequently relegated into the Championship league Division. They only bright part of the season was when they reached the F.A.Cup final in 2010 and lost to Chelsea.

The Mary Rose 1509, HMS Victory 1759 and HMS Warrior 1859 - History

I have decided to create this article about the history of some of the most famous British Warships which can still be found at Portsmouth Dockyard. The three famous ships are Henry VIII's flagship The Mary Rose, Nelson's HMS Victory and The World's first all Ironclad Warship, HMS Warrior.

The Mary Rose

The Mary Rose was built in Portsmouth in 1509. One of Henry VIII's 'great ships', Mary Rose was named after the king's favourite sister Mary and the Tudor emblem the Rose. Typical of the larger sailing ships of the fleet with high castles at the bow and stern, she was one of the first ships with gun ports cut out along the side of the hull for the firing of heavy guns.

Mary Rose had a long career and was frequently in battle against the French. On 10 August 1512 she was part of an English force that attacked the French fleet at Brest. Mary Rose crippled the enemy flagship, bringing down her mast and causing 300 casualties. This was possibly the first battle in the Channel when ships fired their heavy guns through gun ports.

The sinking of the Mary Rose is the event for which the ship is best known. On 19 July 1545 Mary Rose was part of an English fleet that sailed out of Portsmouth to engage the French. She fired a broadside at the enemy and was turning to fire the other broadside when water flooded into her open gun ports and the ship suddenly capsized in full view of Henry VIII watching from the shore. It is not certain what caused Mary Rose to capsize; she was overloaded with extra soldiers and may have been caught by a gust of wind, which made the ship heel over.

The wreck of the Mary Rose was rediscovered in 1968 and before her recovery divers carried out much preparation work. On 11 October 1982 the hull was lifted off the seabed and placed on a cradle before being raised by a giant floating crane. It was then towed back into Portsmouth harbour from where the ship had left on her last fateful journey 437 years before. Today the Mary Rose is preserved in No.3 dock in Portsmouth.

HMS Victory

HMS Victory in Dock without Sails

Ordered by the Navy Board on June 6, 1759, HMS Victory was designed by Surveyor of the Navy, Sir Thomas Slade. Building commenced the following month at Chatham Dockyard under the watchful eye of Master Shipwright John Lock. On October 30, 1760, the name Victory was chosen for the new ship, perhaps in honour of Britain's "Annus Mirabilis" (Year of Victories) in 1759, during the Seven Years' War. The work was completed in 1765, under the supervision of Master Shipwright Edward Allen. Launched on May 7 of that year, the finished 100-gun ship cost a total of £63,176.

Service History:

After completing sea trials, Victory was placed in ordinary as the war had been concluded. It remained in this reserve role until May 1778, when it was first commissioned as the flagship of Admiral Augustus Keppel during the War of American Independence. Two months later, on July 27, Keppel's fleet encountered a French fleet off Ushant and gave battle. Though the First Battle of Ushant was inconclusive, it was Victory's baptism by fire. Two years later, in March 1780, the ship was placed in dry dock and its hull sheathed with copper to protect against shipworm.

Returning to sea, Victory served as Rear Admiral Richard Kempenfelt's flagship during his triumph at the Second Battle of Ushant on December 12, 1781, and later took part in Admiral Richard Howe's relief of Gibraltar in October 1782. With the war's conclusion, Victory underwent a £15,372 refit and had its armament increased. With the beginning of the War of the First Coalition in 1793, Victory became the flagship of the Mediterranean fleet under Admiral Lord Samuel Hood. After participating in the capture (and loss) of Toulon and Corsica, Victory returned to Chatham for a brief overhaul in 1794.

Returning to the Mediterranean the following year, Victory remained in the area until the British fleet was forced to withdraw to Portugal. In December 1796, Admiral John Jervis made Victory his flagship when he took command of the Mediterranean fleet. Two months later, he led the fleet to victory over the Spanish at the Battle of Cape St. Vincent. Growing old, Victory returned to Chatham that fall to be surveyed and have its fate decided. Ruled unfit for service on December 8, 1797, orders were issued to convert Victory into a hospital ship.

With the loss of the first-rate HMS Impregnable in October 1799, Victory's conversion orders were countermanded and new ones issued to repair and restore the ship. Initially estimated at £23,500, the reconstruction project eventually cost £70,933 due to an ever increasingly list of defects in the hull. Completed in April 11, 1803, Victory sailed to rejoin the fleet. On May 16, 1803, Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson hoisted his flag aboard Victory as the commander of the Mediterranean fleet. Serving as Nelson's flagship, Victory patrolled off Toulon as part of the British blockade of that port.

In May 1805, the French fleet under Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve escaped from Toulon. After sailing east first, Nelson learned that the French were heading for the West Indies. Pursuing them across the Atlantic and back again, Nelson finally was able to bottle them up in the Spanish port of Cadiz. When Villeneuve departed Cadiz on October 19, Nelson was able to bring him to battle off Cape Trafalgar two days later. Splitting his force in two, Nelson drove his ships in two columns into the heart of the combined French-Spanish fleet.

Aggressively attacking, the British decimated Villeneuve's fleet, winning one of the greatest naval victories in history. During the battle Victory engaged Villeneuve's flagship, Bucentaure (80) and Redoutable (74). After inflicting heavy damage on Bucentaure, Victory duelled Redoutable with both ships suffering heavy casualties. During the fight, Nelson was shot through shoulder by a marine aboard Redoutable. Taken below, he died three hours later as his fleet was completing the victory. After the battle, the badly damaged Victory transported Nelson's body back to England.

Repaired after Trafalgar, Victory saw service as a flagship in the Baltic and off the coast of Spain. On December 20, 1812, the 47-year old warship was paid off for the last time at Portsmouth. Though the ship was refitted a final time after the war, it remained in ordinary and became the flagship for the Port Admiral in 1824. In 1889, the ship was fitted out for use as the Naval School of Telegraphy and later the Signals School. These remained on board until 1904, when they were moved HMS Hercules and then to the Royal Naval Barracks.

By 1921, Victory was in poor condition and a campaign was started to raise money for the ship's restoration. Moved to the oldest dry dock in the world, No. 2 Dock at Portsmouth, on January 12, 1922, Victory underwent a massive six-year restoration which returned the ship to its 1805 appearance. Victory saw its last wartime action in 1941, during World War II when it was hit by a Luftwaffe bomb which caused some hull damage. Under constant restoration, Victory is still in commission and is open to the public as a museum ship at Portsmouth.

Overview:

Nation: Great Britain

Builder: Chatham Dockyard

Laid Down: July 23, 1759

Launched: May 7, 1765

Commissioned: May 1778

Decommissioned: November 7, 1812

Fate: Preserved as a museum ship at Portsmouth, England.

Specifications:

Ship Type: Ship of the Line (First Rate)

Displacement: 3,500 tons

Length: 227 ft., 6 in.

Beam: 51 ft., 10 in.

Draft: 28 ft. 9 in.

Complement: approx. 850

Speed: 8-10 knots

Armament (at Trafalgar):

Gun Deck: 30 x long 32-pdrs

Middle Gun Deck: 28 × long 24-pdrs

Upper Gun Deck: 30 × short 12-pdrs

Quarterdeck: 12 × short 12-pdrs

Forecastle: 2 × medium 12-pdrs, 2 × 68 pdr carronades

HMS Warrior

HMS Warrior docked outside Portsmouth Dockyard

During the early decades of the 19th century the Royal Navy began add steam power to many of its ships and was slowly introducing new innovations, such as iron hulls, into some of its smaller vessels. In 1858, the Admiralty was stunned to learn that the French had commenced construction of a Wood Mixed iron warship named La Gloire. It was the desire of Emperor Napoleon III to replace all of France's warships with iron-hulled ironclads, however French industry lacked the capacity to produce the needed plate. As a result, La Gloire was initially built of wood then clad in iron armour.

Commissioned in August 1860, La Gloire became the world's first ocean-going ironclad warship. Sensing that their naval dominance was being threatened, the Royal Navy immediately commenced construction on a vessel superior to La Gloire. Conceived by Admiral Sir Baldwin Wake-Walker and designed by Isaac Watts, HMS Warrior was laid down at Thames Ironworks & Shipbuilding on May 29, 1859. Incorporating a variety of new technologies, Warrior was to be a composite sail/steam armoured frigate. Built with an iron hull – the world's first fully iron built warship and Warrior's steam engines turned a large propeller.

Central to the ship's design was its armoured citadel. Built into the hull, the citadel contained Warrior's broadside guns and possessed 4.5" iron armour which was bolted onto 9" of teak. During construction, the design of the citadel was tested against the most modern guns of the day and none were able to penetrate its armour For further protection, innovative watertight bulkheads were added to the vessel. Though Warrior was designed to carry fewer guns than many other ships in the fleet, it compensated by mounting heavier weapons.

These included 26 68-pdr guns and 10 110-pdr breech-loading Armstrong rifles. Warrior was launched at Blackwall on December 29, 1860. A particularly cold day, the ship froze to the ways and required six tugs to pull it into the water. Commissioned on August 1, 1861, Warrior cost the Admiralty £357,291. Joining the fleet, Warrior served primarily in home waters as the only dry dock large enough to take it was in Britain. Arguably the most powerful warship afloat when it was commissioned, Warrior quickly intimidated rival nations and launched the competition to build bigger and stronger iron/steel battleships.

Upon first seeing Warrior's power the French naval attaché in London sent an urgent dispatch to his superiors in Paris stating, "Should this ship meet our fleet it will be as a black snake among rabbits!" Those in Britain were similarly impressed including Charles Dickens who wrote, "A black vicious ugly customer as ever I saw, whale-like in size, and with as terrible a row of incisor teeth as ever closed on a French frigate." A year after Warrior was commissioned it was joined by its sister ship, HMS Black Prince. During the 1860s, Warrior saw peaceful service, its gun battery upgraded between 1864 1867.

Warrior's routine was interrupted in 1868, following a collision with HMS Royal Oak. The following year it made one of its few trips away from Europe when it towed a floating dry dock to Bermuda. After undergoing a refit in 1871-1875, Warrior was placed in reserve status. A ground breaking vessel, the naval arms race that it helped inspire had quickly led to it becoming obsolete. From 1875-1883, Warrior performed summer training cruises to the Mediterranean and Baltic for reservists. Laid up in 1883, the ship remained available for active duty until 1900.

In 1904, Warrior was taken to Portsmouth and renamed Vernon III as part of the Royal Navy's torpedo training school. Providing steam and power for the neighbouring hulks that comprised the school, Warrior remained in this role until 1923. After attempts to sell the ship for scrap in the mid-1920s failed, it was converted for use a floating oil jetty at Pembroke, Wales. Designated Oil Hulk C77, Warrior humbly fulfilled this duty for half a century. In 1979, the ship was saved from the scrap yard by the Maritime Trust. Initially led by the Duke of Edinburgh, the Trust oversaw the eight-year restoration of the ship. Returned to its 1860s glory, Warrior entered its berth at Portsmouth on June 16, 1987, and began a new life as a museum ship.

General:

Nation: Great Britain

Builder: Thames Ironworks & Shipbuilding Co. Ltd.

Laid Down: May 25, 1859

Launched: December 29, 1860

Commissioned: August 1, 1861

Decommissioned: May 31, 1883

Fate: Museum ship at Portsmouth, England

Specifications:

Type: Armoured Frigate

Displacement: 9,210 tons

Length: 418 ft.

Beam: 58 ft.

Draft: 27 ft.

Complement: 705

Power Plant: Penn Jet-Condensing, horizontal-trunk, single expansion steam engine

Speed: 13 knots (sail), 14.5 knots (steam), 17 knots (combined)

Armament:

26 x 68-pdr. guns (muzzle-loading)

10 x 110-pdr. Armstrong guns (breech-loading)

4 x 40-pdr. Armstrong guns (breech-loading).

Havant Market Town – England and It's History

The history of Havant is entwined with the history of Portsmouth which extends almost two thousand years. Havant used to be famous for it's Parchment and Glove making during the lst 500 years.

Havant was once Hama's funta. Funta meant spring. A man named Hama once owned this area of Hampshire. Denvilles derives its name from the Saxon word Denn which meant woodland pasture for pigs. (The 'villes' was added much later). The Saxon word 'tun' meant farm or estate. Brockhampton was brook home farm. Lang is the Saxon word for long so Langstone was probably once a village by a long stone.

At the time of Domesday Book (1086) Havant was a village with a population of about 100. It would seem tiny to us but towns and villages were very small in those days. Havant had 2 mills, which ground grain to flour to make bread for the villagers. One mill was Southwest of the town. The other was probably in Langstone.

St Faith's Church in Havant dates from the 12th century although it was largely rebuilt in the 19th century.

In the Middle Ages Havant grew from a large village into a small market town. In 1200 Havant was given a charter (a document granting the townspeople certain rights). Among was the right to have a weekly market. From 1451 Havant also had an annual fairs. (In the Middle Ages fairs were like markets but they were held only once a year and would attract buyers and sellers from a wide area). Later (the exact date is unknown Havant had a second annual fair). However to us Havant would seem tiny. It probably only had a population of several hundred.

In the late Middle Ages and 16th century there was a wool industry in Havant but it declined in the 17th century. However there was an important industry tanning leather in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. Havant had fellmongers (people who dealt in animal skins). Havant was also know for its glove making industry.

The little town of Havant was also known for parchment making. Parchment was made from the skins of sheep, goats or calves. It was used as a writing material instead of paper. Water was used to make parchment (the skins were soaked in it). The spring in Havant gave pure water, which made bright white parchment. So the parchment made in Havant was of a high quality.

For centuries Langstone was a small port. Even in the 19th century there was a coastal trade there. (In the past goods were often taken by ship along the coast from one part of the country to another instead of being transported overland). Langstone watermill was built in the 18th century to grind grain to flour.

Meanwhile Warblington Castle was built around 1525. However in 1643 during the civil war parliamentary soldiers destroyed most of it.

Then in 1761 Havant was severely damaged by a fire but it was soon rebuilt. In 1762 the road from Portsmouth to Chichester was turnpiked. (A turnpike road was privately owned and maintained and you had to pay to use it.) Stagecoaches travelling between the two towns stopped at Havant.

Nevertheless in 1801 Havant was a very small market town. It only had a population of 1,670. In 1801 Havant was smaller than Petersfield.

Havant grew steadily during the 19th century but in 1901 it still had a population of less than 4,000. Meanwhile in the 19th century the industry of parchment making continued to prosper in Havant. In 1919 the Treaty of Versailles was written on parchment made in Havant. However the parchment making industry in Havant ended in the 1930s. In the 19th century another industry in Havant was brewing.

As Havant grew in the 19th century its amenities improved. Hayling Bridge was first built in 1824. In 1847 Havant was connected to both Portsmouth and Chichester by railway. From 1867 a railway ran from Havant to Hayling Island. From 1859 Havant was connected to London by railway. Railway stations were built at Bedhampton (1906) and Warblington (1907), to serve those two rapidly growing areas.

From 1855 Havant had a supply of gas (for lighting). Havant gained its first police station in 1858. From 1870 Havant had a piped water supply. Also in 1870 Havant Town Hall was built.

In 1871 a fire brigade made up of volunteers was formed in Havant. However in 1871 the 2 annual fairs were abolished. Havant Park opened in 1889. In 1894 Havant became an urban district council.

Conditions in Havant continued to improve during the 20th century. A cinema opened in Havant in 1913. In 1970 the building became Havant library. (The library moved to the Meridian Centre in the 1990s).

By 1949 the population of Havant was about 8,000. In 1926 remains of a Roman villa were found south of Havant.

The War Memorial Hospital opened in 1929. Havant railway station was rebuilt in 1938. Park Road was also built in 1938.

Havant watermill, which stood for centuries just outside the town, closed in 1934. It was demolished in 1958.

Havant Churches

· From 1951 Roman Catholic mass was celebrated in a Nissen hut.

· A Catholic chapel was built in Dunsbury Way in 1955.

· A Methodist church was built in Botley Drive in 1956.

· The first Baptist Church in Leigh Park opened in 1957.

· St Francis Church was built in 1963.

· St Albans in Westleigh was built in 1966.

Building Projects

· Market Parade shopping centre was built in 1961-62.

· In 1963 the railway to Hayling Island closed.

· Havant Police Station was built in 1964.

· Havant By-pass was built in 1965.

· A swimming pool was built in Havant in 1974 and Havant Arts Centre opened in 1978.

· Meanwhile in 1974 Havant changed from being an Urban District Council to a Borough and gained a mayor. A Civic Centre opened in 1977.

· Havant Museum opened in 1979.

· Furthermore a hypermarket opened in Havant in 1980.

· Then in 1982 a leisure centre opened in Havant.

· Part of West Street was pedestrianised in 1983 and a private hospital was built in 1984.

· The first shops moved into the Meridian Centre in 1991.

Parchment making in Havant ended in 1936. Glove making ended in 1960. However after 1945 new industries such as light engineering and plastics came to Havant. In the 1950s land in Brockhampton was set aside for industry. In the late 1950s an industrial estate was built at Westleigh. Kingscroft Industrial Centre opened in 1984.

Chichester Market Town – England and it's History

The history of Chichester is entwined with the history of the Roman Invasion of 43AD and extends back almost two thousand years. The time when the Roman first recognized its strategic significance and built the fort and now the home to a thriving Market Town Shopping centre.

In 43 AD the Romans invaded Britain and about 44 AD they built a fort on the site of Chichester. It was by a source of water (the river Lavant) and close to a harbour so supplies could be brought by ship from France. Soon the Roman army moved on.

The king of the local Celtic tribe, Cogidnubus, co-operated with the Romans rather than resist them. The Romans left him as a puppet king of Sussex. After the Romans had left the fort Codignubus decided to take it over and make it into a town. The Romans called Chichester Noviomagus, which means new market place.

Roman Chichester was built on a grid pattern. The main streets formed a cross, which remains today as North, South, East and West Streets. In the centre of the town was the forum, a marketplace lined with shops and public buildings. People in Roman Chichester used cesspits and obtained their water from wells but in the streets there were drains for rainwater.

In the late 2nd century a ditch was dug around Roman Chichester and earth ramparts were erected with a wooden palisade on top. Early in the 3rd century stone walls were built. In the 4th century they were strengthened with bastions, semi-circular towers. A ballistae, a form of giant crossbow, could be mounted on one.

About 80 AD an amphitheatre was built beside Roman Chichester. It would have had tiers of wooden seats for about 800 people. On special occasions gladiators fought to the death but usually the entertainment consisted of cock fighting and bear baiting. (The animal was chained and dogs were trained to attack it).

Another pastime was going to the public baths, which stood near Chapel Street. In Roman times going to the baths was not just to get clean but was also a way to socialise, the Roman equivalent of going to the pub. In Roman Chichester there was also a temple to Neptune and Minerva at the junction of North Street and Lion Street.

In Roman Chichester rich people lived in houses with glass windows, mosaic floors, painted murals on their walls and even a form of central heating called a hypocaust. Of course, most people were very poor and had none of these things.

In Roman Chichester there were carpenters, blacksmiths, bronze smiths, potters and leatherworkers. There were also people who made combs and boxes from bone. In the 4th century Chichester declined along with the rest of Roman Britain. The last Roman soldiers left Britain in 407 AD.

In the late 5th or early 6th century the Saxons arrived. Chichester is named after a Saxon called Cissa. The Saxons called any group of Roman buildings a ceaster. They called this town Cissa's ceaster. It changed to Cisscester then finally to Chichester.

Nothing is known of what happened to Chichester till the late 9th century. At that time Alfred the Great created a network of fortified places across his kingdom where men could gather when the Danes attacked. Often he used old Roman towns or forts. Chichester was made a burgh.

The strategy worked. In 894 the Danes landed in West Sussex but men from Chichester and the surrounding area went out to meet them. They routed the Danes, killing several hundred men and capturing several ships. This was Chichester's finest hour.

However the burgh of Chichester was not just a stronghold. It was also a flourishing town with a weekly market. In the 10th century there was a mint in Chichester so by then it must have been an important community.

At the time of the Norman conquest Chichester probably had a population of less than 1,500 people. That seems very small to us but remember that most people lived in tiny villages of about 100-150 people. Any settlement with over 1,000 inhabitants was a fair sized town. By the 13th century Chichester had probably grown to about 2,500 people. Still very small by our standards but it would have been a lively place especially on market days.

The South-eastern part of Chichester belonged to the Archbishop of Chichester belonged to the Archbishop of Canterbury. This area was called the Palantine. The word palantine means 'of the palace' because this area belonged to the 'palace' of the Archbishop. In time the name became corrupted to Pallant.

The Normans built a motte and bailey castle in Chichester in what is now Priory Park. This was a wooden fort on an artificial hill (a motte) surrounded by a ditch and rampart with a wooden palisade (a bailey). Later the castle may have been rebuilt in stone.

In 1075 the local bishop moved his bishopric from Selsey to Chichester, changing its history forever. Chichester cathedral was built after 1091 and it was consecrated in 1108. Unfortunately this building was severely damaged by fire in 1114 and it was rebuilt. Another fire devastated the cathedral in 1187 and it again had to be rebuilt. Chichester Cathedral originally had a bell tower but in the early 15th century this was moved to a separate tower called a campanile. The cathedral was given a spire to replace it.

There were weekly markets in Chichester but from 1108 the bishop was given the right to hold a fair. (A fair was like a market but was held annually and attracted buyers and sellers from all over Southern England). The fair was held for 8 days each October. It was called the Sole fair after a sloe tree, which grew in field by Northgate.

In 1125 King Stephen gave Chichester its first charter (a document confirming its rights and privileges). In the Middle Ages merchants were organised into bodies called guilds which looked after their interests. In Chichester the merchant's guild owned underground vaults where perishable goods could be stored in a cool environment. These vaults still exist.

In 1216 there was civil war and some barons invited a French prince to come and be king of England. His French soldiers occupied the castle. The French prince was eventually persuaded to go home and the castle was demolished.

In the 13th century it is recorded that wool was exported from Chichester (from Dell Quay). At that time wool was by far England's most important export. The king tried to control the trade by only allowing certain ports to export wool. These ports were called staples. In 1353 Chichester was made a staple port. It might seem surprising now but in the Middle Ages Chichester was one of England's most important ports. Chichester Harbour was deeper than it is today. (It has since silted up). Until 1800 ocean-going ships could sail up to Dell Quay.

There were many cloth workers in Chichester. After it was woven wool was cleaned and thickened. This was done by pounding it in a mixture of water and clay. The wool was pounded by wooden hammers worked by watermills. This was called fulling. The watermills were called fulling mills. There were several in Chichester on the Lavant. There were also weavers and dyers in the town.

There was also a needle making industry in Chichester in the Middle Ages. There were also the same craftsmen found in any town. These included brewers, bakers and butchers. Crooked S Lane was once called The Shambles and was full of slaughterhouses. To us it would seem very unhygienic. Butchers threw offal into the street.

Other craftsmen in Chichester included blacksmiths, carpenters, coopers, wheelwrights, cobblers and other leather workers who made saddles and gloves. There was also a tanning industry in Chichester. Tree bark was soaked in fresh water to extract tannin to tan leather.

In the Middle Ages Chichester produced its only saint. Richard was Bishop of Chichester in 1245-1253. He is now patron saint of Sussex.

In the 13th century the friars arrived in England. The friars were like monks but instead of withdrawing from the world they went out to preach and help the poor. In Chichester there were Dominican friars (called black friars because of the colour of their costumes). They lived in the South East of the town where St Johns church is today. They owned the land around the friary from the town wall up to where Baffins Road and Friary Lane are today.

From about 1230 Franciscan friars (known as grey friars) lived in buildings in St Martins Square. In 1269 they moved to the site of the castle. The site in St Martins Square was taken over by St Marys Hospital. This establishment previously existed in South Street. (In the Middle Ages the only hospitals were manned by monks who cared for the sick as best they could). There was also a leper hospital outside the Eastgate. Spitalfields Road is named after some fields it owned. (It was originally called Hospitalfield Lane). In 1497 the Prebendal School was founded (although a school attached to the cathedral had probably existed much earlier).

In 1501 Bishop Storey erected Chichester market cross. If you wanted to sell goods at the market you had to pay a toll. There were some poor peasants who only had a few eggs or a few vegetables to sell. The bishop said anyone could sell things at the market and not pay a toll provided they could stand under the cross.

In 1538 Hentu VIII closed the friaries in Chichester and sold their property. A mansion was built on the site of the black friary in East Street and the surrounding land became its gardens. The grey friary was demolished but its church survived and in 1541 it was sold to the corporation and made the guildhall.

During the 16th century Chichester declined in importance. The wool trade declined. The main exports became wheat and malt. Malt is used in brewing. It is made from barley. The barley was soaked in water then laid out to dry then baked. Malt from Chichester was 'exported' along the coast to other parts of England. Other industries in Chichester were brewing and tanning.

There is a story that when Queen Elizabeth visited Chichester she said: 'it is a little London' and one of the streets in the town has been called that ever since. It isn't true as Little London is shown on 15th century maps. It may have got its name because merchants from London lived and worked there.

In 1578 the streets of Chichester were paved for the first time by an Act of Parliament.

In 1588 the people of Chichester provided a small ship called The John to fight the Spanish Armada.

Also in 1588 two Catholic priests were tried for treason in Chichester. (Priests were regarded as foreign agents). Ralph Crockett and Edward James were hung drawn and quartered at a spot west of the town.

In 1625 a brewer named William Cawley built some almshouses for 12 'decayed' (impoverished) tradesmen.

In 1642 came civil war between king and parliament. At that Chichester was a town of about 3,000 people and their loyalties were divided. The bishop and most of the clergy supported the king while most of the merchants supported parliament. At first it was not clear which way Chichester would go. Then the local landowners, the gentry, decided the issue. A force of 600 men, 200 cavalry and 400 infantry rode into Chichester and took if for the king. There was no resistance.

However parliament quickly sent an army to besiege the town. They fired cannons from the North, then the West. Finally they fired them from the East. At that time there was a little suburb outside Eastgate, around St Pancras church, where people made needles. (This is why the road there is called the Needlemakers today). The defenders set the houses in the suburb on fire but the parliamentary soldiers set up a cannon on a church tower and fired over the wall. Chichester surrendered and remained in parliamentary hands for the rest of the war.

Most of the houses in Chichester in the early 17th century were made of wood with thatched roofs. However tiled roofs gradually replaced them. In 1687 a by-law banned thatched roofs because of the risk of fire. In the late 17th century people in Chichester began to build houses in brick. Westgate House was built in the 1690s. (It is sometimes incorrectly called Wren House. In fact Wren did not build it).

In the 18th century the population of Chichester was around 4,000. It started to rise towards the end of the period but was still less than 5,000 at the time of the first census in 1801.

By the 18th century Chichester had dwindled to being a quiet market town. In 1724 Daniel Defoe wrote that Chichester was: 'not a place of much trade, nor is it very populous'. This quiet little town was largely rebuilt during this century. Many houses were rebuilt in brick. The bricks were made using local clay. Brick making became an important local industry.

Among the houses built at this time was Dodo House, which was built in the Pallant for Henry Peckham, a wine merchant, in 1712. It gets its name because Peckham wanted ostriches carved on columns (ostriches appear on his family coat of arms). However the person who carved them had probably never seen an ostrich and they are said to look more like dodos.

In 1731 Council House was built in North Street. As it has a lion on its roof a nearby street became known as Lion Street. The old Guildhall then became a magistrates court.

To ease the flow of traffic into Chichester West, North and South gates were demolished in 1773. Eastgate was demolished in 1783. Travel to and from Chichester was made easier when turnpike roads were built. You had to pay to use them but at leas they were properly made up and were an improvement on dirt tracks. A turnpike road to London opened in 1748 and one to Portsmouth opened in 1762.

There were some improvements to Chichester during this era. In 1726 four clocks were added to the cross. Chichester gained its first theatre in 1764. It opened in an old warehouse in Theatre Street. In 1791 a purpose built theatre was erected there. In 1779 Chichester gained its first bank. Then in 1791 an Act of Parliament set up a body of men called the Paving Commissioners. They had power to pave and clean the streets and to remove 'nuisances' such as overhanging shop signs and bay windows that obstructed narrow alleys.

Chichester was a town of craftsmen working in their own workshops with an apprentice. There were carpenters, bricklayers and glaziers, blacksmiths, wheelwrights, coopers, saddlers, tailors and shoemakers. There were also bakers, brewers and grocers and gunsmiths and clay pipe makers. On the other hand the old industry of needle making died out completely by the end of the century.

In 1750 a grocer named Mr. Shippam opened a warehouse in West Street. He sold cheese and meat to the navy in nearby Portsmouth. In 1782 he opened a shop in East Street.

In 1784 a new charity was formed in Chichester. A dispensary for sick poor people opened in Broyle Road. The poor were given free medicines.

In the very early years of the century, during the Napoleonic Wars, a barracks was built in Chichester. Although Chichester was a small town it grew in size in the 19th century simply because the population of Britain quadrupled. In the first years of the 19th century Somerstown was built outside the city walls. More building took place in the South East corner of the town. There was still a manor house with gardens till 1809 when the land was sold for building. The new area was called Newtown (today this is the name of a single street). St John's Church opened in 1813.

In the early 19th century the market in Chichester was becoming very congested. On market days West Street was full of livestock for sale. There were also people selling food. To ease the congestion it was decided to erect a building where people could sell things like butter, cheese and vegetables separately from the livestock market. In 1808 the Buttermarket was built for this purpose. At the same time railings were erected around the market cross. However having a market in East Street still caused a lot of congestion in the town and impeded traffic. Therefore, in 1871, a new cattle market opened outside the Eastgate.

In 1833 the Corn Market was built. In the late 19th century the front part of this building was used as a theatre and in the early 20th century as a cinema. Chichester gained gas light in the 1820s. Then, in 1826, the dispensary for poor sick people became Chichester Infirmary (forerunner of St Richard's Hospital). Graylingwell Hospital opened in 1897.

Chichester gained its first police force in 1836. The first police station was by the Eastgate. At first the town police force was separate from that of West Sussex but they joined together in 1889. In that year the police station moved to Southgate.

In Chichester drunks were put in the stocks. The last person to suffer this punishment was sentenced to 2 hours in 1852.

From 1875 Chichester had a piped water supply. However it was later than most other towns in building drains and sewers. Chichester had a reputation in the late 19th century as being an unhealthy and unsanitary place. Most people in the town used cesspits. Some used buckets, which they emptied into the Lavant. Yet many people in Chichester were reluctant to build a network of drains and sewers because of the expense. They were finally built in 1893-96. The worst area of Chichester was St Pancras. This was the poorest area and was full of poverty and overcrowding.

In 1846 Chichester was connected to Brighton by railway and in 1847 it was connected to Portsmouth. In 1881 a branch line to Midhurst opened. Then in 1897 a light railway to Selsey opened. There was also a canal from Portsmouth to Arundel, which was completed in 1855. However the canal was not a success and the last section, from Birdham to Chichester, closed in 1906.

In 1850 Bishop Otter Teacher Training College opened.

In 1861 the spire of Chichester Cathedral collapsed during a thunderstorm and had to be rebuilt.

In 1892 Shippams opened a meat paste factory at Eastgate.

By the beginning of the 20th century the population of Chichester had reached about 9,000. It rose to about 12,000 by the time of the First World War partly because Summersdale was built North of the town. By 1939 the population of Chichester had risen to about 16,000.

In 1909 Chichester gained electric street light. In 1910 Chichester gained its first cinema in West Street.

Chichester High School for Boys opened in 1908. The High School for Girls opened in 1910.

In 1913 the infirmary became The Royal Sussex Hospital. It moved to its present site in 1937.

In 1918 Priory Park, which was still private land, was given to the council for public use. In the 1920s the first council houses were built in Chichester. By 1939 481 of these had been built. A new police station was built in Kingsham in 1937. The same year Chichester by-pass opened.

During World War II there were 3 bombing raids on Chichester. Bombs were dropped on Basin Road in 1941, on Chapel Street and St Martins Street in 1943 and on Arndale and Green Roads in 1944. Furthermore in May 1944 after being badly damaged by enemy fire over France an American bomber crashed on the site of the old Roman amphitheatre. (The pilot and crew managed to bail out in time but could do nothing to prevent the plane crashing).

After 1946 the Whyke Estate was built and, in the early 1950s, Parklands estate was built.

In 1957 Chichester was twinned with Chartres. A new ring road was built in 1958-1966.

In the early 1960s the area called Somerstown was demolished and rebuilt, as many of its houses were substandard. Yet this was controversial, as Somerstown was a self-contained community with its own shops. The rebuilding broke up that community.

In 1962 Chichester peacheries closed and houses were built on the site. Houses were also built North of Bognor Road. By 1971 the population of Chichester had reached 21,000.

Chichester Festival Theatre opened in 1962. In 1963 Chichester Museum opened in an old corn store.

In 1961 a new railway station was built and in 1965 a new bus station. In 1964 a training centre for military police opened on the site of an old army barracks. In 1967 a new library opened. The same year a swimming pool opened outside Eastgate.

In the 1980s shopping arcades were built in Chichester, Northgate Arcade and Alsmhouse Arcade. Westgate Leisure Centre opened in 1987. In 1989 a new record office opened in Chichester. Chichester livestock market closed in 1990. A new Tourist Information Centre opened in 1993.

Today Chichester is a flourishing town and it is growing steadily. Today, in the 21st. Century the population of Chichester is 26,000.

A to Z of English and Welsh Market Towns

The Celts who lived in Britain before the Roman invasion of 43 AD could be said to have created the first towns. Celts in southern England lived in hill forts, which were quite large settlements. (Some probably had thousands of inhabitants). They were places of trade, where people bought and sold goods and also places were craftsmen worked. The Romans called them oppida.

From the 5th century Angles, Saxons and Jutes invaded England. At first the invaders avoided living in towns. However as trade grew some towns grew up. London revived by the 7th century had a population of between 10 – 20,000 (although the Saxon town was, at first, outside the walls of the old Roman town). Southampton was founded at the end of the 7th century. Hereford was founded in the 8th century. Furthermore Ipswich grew up in the 8th century and York revived.

In the Middle Ages most towns were given a charter by the king or the lord of the manor. It was a document granting the townspeople certain rights. Usually it made the town independent and gave the people the right to form their own local government.

In 1348-49 British towns were devastated by the Black Death. However most of them recovered and continued to prosper. Another danger in medieval towns was fire and many suffered in severe conflagrations.

In the 18th century conditions in most towns improved (at least for the well off). Bodies of men called Improvement Commissioners or Paving Commissioners were formed with powers to pave, clean and light the streets (with oil lamps). Many towns also employed night watchmen. Most towns gained theatres and private libraries. However despite some improvements 18th century towns would seem dirty and crowded to us.

From the late 18th century the industrial revolution transformed Britain. Many villages or small market towns rapidly grew into industrial cities.

At the end of the 19th century transport in towns was improved. From c.1880 horse drawn trams ran in the streets of many towns. At the beginning of the 20th century they were replaced by electric trams.

Below is a List of all the Market Towns in England and Wales; with the Days of the Week when the market takes place Note: m. signifies Monday; t. Tuesday; w. Wednesday; th. Thursday; f. Friday; and s. Saturday.

Those Places printed with English* Letters, are Cities; those with italic Letters, Shire Towns.

[*Editor: Since Web Browsers vary in the fonts they have available, I have substituted bold type to indicate Cities.

Abbotsbury in Dorsetshire, th.

Aberforth, Yorksh, w.

Abergavenny, Monm. t.

Aberistwith, Cardig. m.

Abingdon, Berks, m. f.

Ailesbury, Bucks, s.

Aldborough, Suff. s.

Alesham, Norf. s.

Alford, Linc. t.

Alfreten, Derbysh. m.

Alnwick, Northumb. s.

Alresford, Hantsh. th.

Alstonmore, Cumberl. s.

Altrincham, Chesh. t.

Ambleside, Westmorl. w.

Amersham, Bucks. t.

Ampthill, Bedf. th.

Andover, Huntsf. s.

Apulby, Westmorl. s.

Arundel, Suff. w. s.

Ashbourn, Derbysh. s.

Ashburton, Devon, s.

Ashby de la Zouch, Leic. s.

Ashford, Kent, s.

Atherston, Warwic. t.

Attleborough, Norf. th.

Aubourn, Wilts, t.

Aukland, Durh. th.

Aulcester, Warwic. t.

Autrey, Devon, t.

Axbridge, Somerset. th.

Axminster, Devon, s.

Aye, Suff. s.

Bakewell, Derbysh. m.

Bala, Merionethsh. s.

Baldock, Herts. th.

Bampton, Oxon, w.

Banbury, Oxon, th.

Bangor, Carnarv. w.

Barking, Ess. w.

Barnet, Herts, m.

Barnard Castle, Durh. w.

Barnsly, Yorksh. w.

Barnstable, Devon, f.

Barton, Lincol. m.

Barwick, Northumb. s.

Basingstoke, Hant. w.